By Jahsaiah Moses, Kimberly Lara, Claire DuBois, and Lauren Tanel

Land Acknowledgment

As Haverford College students engaged in the creation of the Friends of Cobbs Creek organization, we are committed to work that acknowledges the history of the natural environment we inhabit and focuses on the local indigenous peoples who have acted as stewards to this land for generations and still do today. “Lenape” is not the name of a single tribe, but includes the three original and separate bands: the Unami, the Munsee, and the Unalachtigo, otherwise known as the Nanticoke. The following acknowledgement is adapted from a document created by a group of student strike organizers: Wahab Bajwa, Claudia Ojeda, Erica Kaunang, Brandon Pita, and Jasmine Reed.

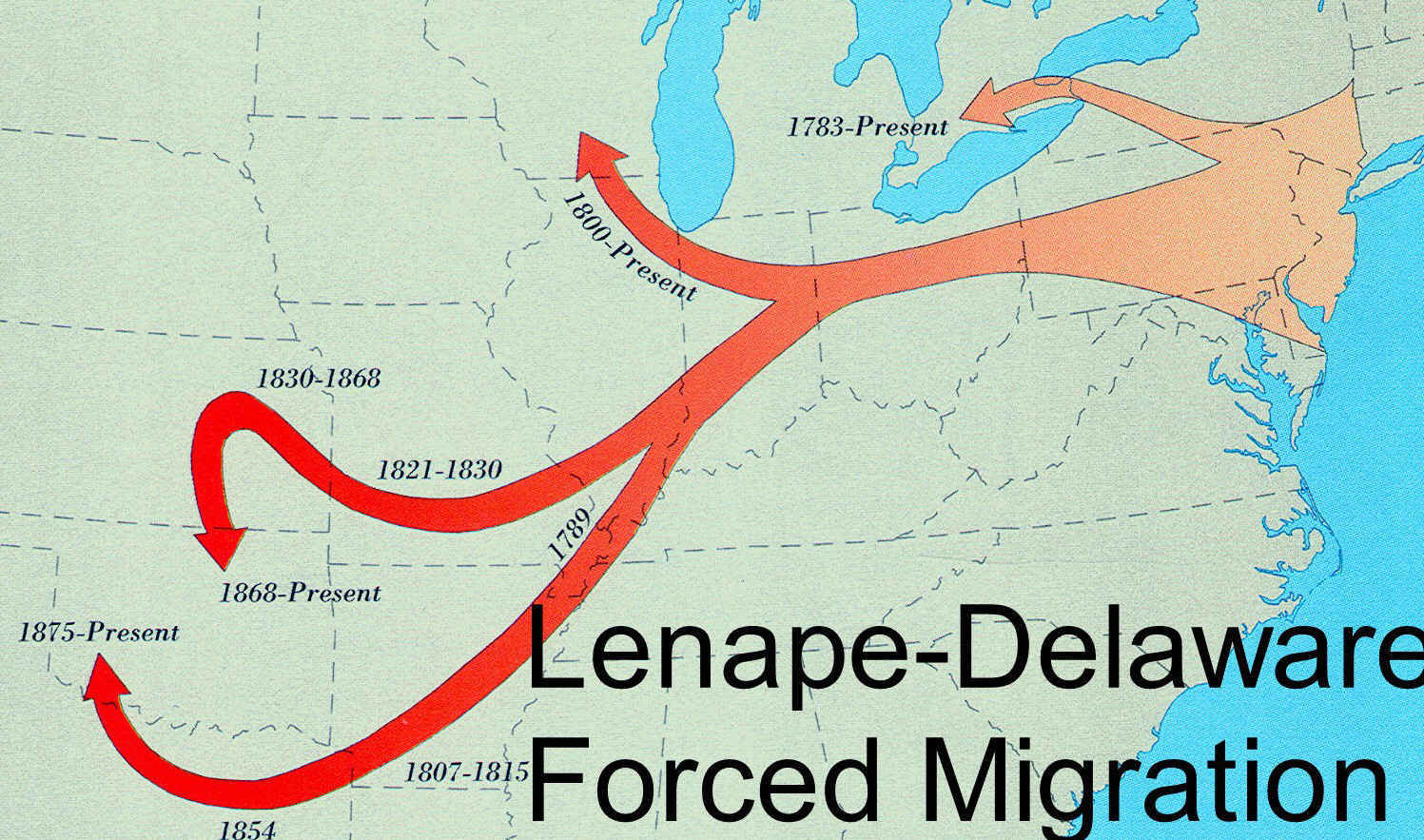

As members of the Haverford College community, it is our obligation to acknowledge that the Haverford College campus is located on land that was occupied by Lenni Lenape people for over 10,000 years. Along with this, we must also acknowledge the implicit colonial legacy of the institution, which includes the displacement of Lenape people in Oklahoma, Wisconsin, Kansas, and Ontario. This involved the forcible removal, acts of disenfranchisement, and genocide, which resulted in a local population reduction of Lenape from 20,000 to 4,000.

Therefore, Haverford College, as a Quaker institution, has a deep colonial legacy and we must clearly acknowledge the college’s contribution to these violent histories along with our responsibility to build a fuller understanding of the implications of these histories. We must recognize the ways in which our privileges have come at the cost of the oppression of others, and we must discern our own responsibilities in addressing these injustices following the lead of Lenape, Nanticoke-Lenni, Ramapough Lenape, and other Lenni Lenape tribes and nations. Upholding this acknowledgement means the creation of a decentralized collective with equitable access to resources because it is impossible to manage colonized land without addressing it’s colonial history. [1]

Settler Story

As a historically Quaker institution situated on Lenni Lenape land, the Haverford College community has a responsibility to understand the active role the school played and continues to play in these acts of violence and erasure.

Quakers first made contact with the Lenape in 1677 when William Warner arrived in so-called Western Philadelphia on land inhabited by the Unami band. Five years later William Penn laid claim to these lands, which were given to him by King Charles II of England with an attempt to establish a safe place in the New World for Quakers who were facing persecution.

William Penn’s interactions with the Lenape were peaceful overall; he practiced Quaker principles of goodwill and friendship as he believed they were children of God. He made purchase agreements with the Lenape and took ownership rights over the land but did not allow for land where Lenape villages were located to be sold. The Legacy of Penn’s treaty of friendship is still celebrated today by the Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania.

These peaceful relations did not last long after Penn’s death and the Lenape lost their claims to their land in the “Walking Purchase” of 1737 where Penn’s sons reinterpreted and manipulated an outdated agreement Penn had made with the Lenape. This act of dispossession added sixty-five miles to the north and west of the earlier purchase agreements. [2] The Walking Purchase began a series of migrations by the Lenape as they were continually displaced due to settler Westward Expansion.

Religious influence

Before the arrival of European settlers in Lenape inhabited regions, the Lenape followed certain beliefs. Their faith was not organized like Christian denominations. Instead, the Lenape believed they were kin with all of creation. The ‘living’ was gifted from the Creator and the kin spirit. Kin share resources with each other and guests. The Lenape people welcomed guests in a reciprocal kinship.

The different European cultural groups who settled in the Delaware area attempted to convert the Lenape people before the arrival of the Quakers. Unlike the previous cultural groups who clashed with the Lenape, the Quakers and the Lenape had similar beliefs which aided the Quakers in gaining trust from some Lenape people. [3]

The role of religion initially played a role in the colonization of the land. The attempts to convert the Lenape peoples to follow Christian faith was not successful. Upon the arrival of Penn and fellow European settlers, more Lenape people began to accept the Christian faith to unite with the Quakers who were infiltrating the land. They mimicked the ‘praying towns’ existing in New England for the Evangelical Natives. The Lenape people attended worship and native children began attending schools which indoctrinated them into European Quaker assimilation. Although the European settlers congregated with the Natives for this ‘educational’ purpose, they were still threatened by the large population of Natives in the same area. [4]

Lenape Legacies: Still Alive Today

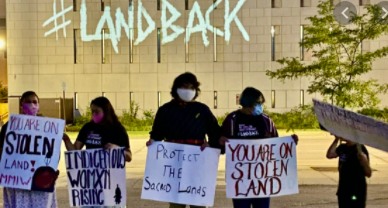

Today descendant’s of the Lenni-Lenape are living in Philadelphia, Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri, Canada, Ontario, and New Jersey. According to the 2010 Census, “13,000 residents of the city identified as Native American Lenape descendants, along with those of Cherokee, Navajo, Cree, Seminole, and Creek tribes, as well as many others, call Philadelphia home” [5]. They are working to keep their culture alive including their land, language, arts, and ceremonies. An example, The Lenape Nation of Pennsylvania established a cultural center that is an educational, cultural, and historical outreach center.

The outreach center helps people understand who they are, their culture, and their history. Today they continue to fight for sovereignty, civil rights, and the health and well-being of their people [6]. The story of the Lenni-Lenape did not end with the removal of their land. It is important to know that there is not only the Lenni Lenape tribe but many Native American tribes that are alive and well and continue to actively fight for their civil rights in the United States.

Envisioning a More Just, Equitable, and Collaborative Future

As a newly imagined stewardship organization, we are looking forward to laying the foundation of a trusting and sustainable community friends group. We acknowledge that our work has only just begun, but anticipate a future of collective action. In order to achieve our goals of creating an organization that benefits each individual and stakeholder, we must first…

- … understand that our history is our future. By laying forth here the information presented above, we aim to deconstruct patterns of colonial erasures by honoring and uplifting those indigenous stories.

- … value love for and repairing of culture rather than centralizing trauma.

- … motivate towards achieving various methods of reparation for Lenape peoples and their descendants: restitution, compensation, self-determination, and guarantees of non-repetition.

- … support place-based education. This is a form of knowledge distribution that understands the particularity of our ecological home, implements decolonial mapping strategies and new ways of categorizing environments, and is empowered to change the systems that govern us and govern our more-than-human environment.

Get involved: local groups, organizations, and community groups

References

- “Letter to President Raymond and Dean Bylander.” HC Strike 2020 Statement and Demands, October 29, 2020. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1u3kg_XDs5ZHH4ma_hL0rlEn5SrQdfbHT9tRh8UE1zcY/edit#heading=h.ffhefbgwshw6.

- The Original People and Their Land: The Lenape, Pre-History to the 18th Century, Part of West Philadelphia Before the 20th Century 20th Century Social and Economic Trends. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://collaborativehistory.gse.upenn.edu/stories/original-people-and-their-land-lenape-pre-history-18th-century.

- “The Vision of William Penn.” Stories from PA History, by Steven Gimber, Stephanie Hurter, and Charles Hardy III, West Chester University. ExplorePAhistory.com, https://explorepahistory.com/story.php?storyId=1-9-3&chapter=3.

- “Strategies of Survival and Revenge.” Lenape Country: Delaware Valley Society Before William Penn, by Jean R. Soderlund, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015, pp. 177-195.. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.cttl3xlnzp.12.

- “Indigenous Peoples of Philadelphia”, American Library Association, December 2, 2019. http://www.ala.org/aboutala/offices/diversity/philadelphia-indigenous (Accessed December 17, 2020) Document ID: 7bb8a80c-e12a-4b91-acd0-ed8c896a11eb

- “The Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape An American Indian Tribe .” Our Tribal History…, 17 Dec. 2020, nanticoke-lenape.info/history.htm.